TV on the Radio – Cat’s Cradle,

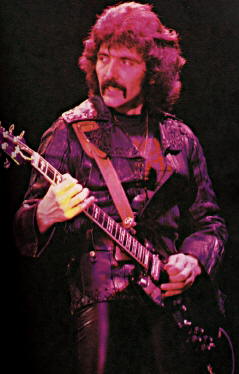

It rained buckets on Sunday, which no doubt contributed to the giddy atmosphere building in anticipation of TV on the Radio’s set at Cat’s Cradle. As the familiar, mural-adorned room began to fill with kids of all stripes – skirted and booted hipster gals, UNC students, bespectacled males who all vaguely resembled TVOTR producer and guitarist

Dave Sitek –

With the crowd warmed up and the exodus to the smoking patio restructuring the floor somewhat, I secured a reasonably close, not-too-off-center spot and waited. At exactly

Adebimpe’s energy as a frontman was astonishing, and he seemed to have struck an improbable balance between chaos and precision: he careened wildly about the stage, but his free hand’s gestures were sharp and committed and he never missed a lyric, even when out of breath. The vocals were impressive throughout the set. In the best moments, the twinning of Adebimpe’s strong lead with Kyp Malone’s falsetto was hair-raising.

As “The Wrong Way” was a different song without its studio production elements, “Dreams” was similarly stripped of its more synthetic qualities and given the rock treatment. It took a little time to adjust to this different side of the band, but when the wall-o’-guitars hit hard and Tunde hit the fantastic line “Leave your treadmill power trip behind,” I was sold.

TV on the Radio is difficult to pin down into a genre classification, but “art rock” might be the most accurate term, not due to any pretentious attitude, but rather cerebral sensibilities and dense sonics. Their records are constructed and arranged with infinite creativity and intuitive experimentalism. Live, these production qualities are not so much lost in translation as set aside, as the band tears its songs apart with visceral attack and boundless enthusiasm. This is still art rock – the art isn’t in the audio trappings, it’s in the songwriting and the vision of the band members.

After a brief conversation with the audience in which he confessed to being “a little” inebriated, and asked whether Cat’s Cradle was technically in Chapel Hill or “Carlsboro,” Adebimpe proceeded to go apeshit on a juiced-up run through “Wolf Like Me.” This was the only song that absolutely everybody seemed to know, and given its clever video’s MTV2 and YouTube exposure, that’s not surprising. But popular doesn’t mean bad, and if TV on the Radio have gotten sick of playing “Wolf” on late night, it doesn’t show.

The set’s latter half offered some sonic variety as bassist Gerard Butler manned a deck of synths and constructed oceans of echo and ghostly harmonies around some of the spacier numbers from Return to Cookie Mountain, with the controlled din accentuating “Dirtywhirl” in particular.

The set ended almost precisely on the hour, and an encore followed about ten minutes later, with the after-partying Noisettes taking the stage to join in on hand percussion. As Adebimpe and company skipped through the playful “A Method,” the drum circle mentality made perfect sense, and seemed to symbolize the something wonderfully right about the experience of watching a group of musicians in a hot, cramped room full of strangers.

They closed it all with “Staring at the Sun,” playing one of their most quintessential tunes at breakneck pace, sloppy, dirty, and saturated with distortion. Early in the set, it would have felt cheap, but at that moment it felt perfect.